“There are certain things that should be reserved for an offline space where the entity can't find them.”

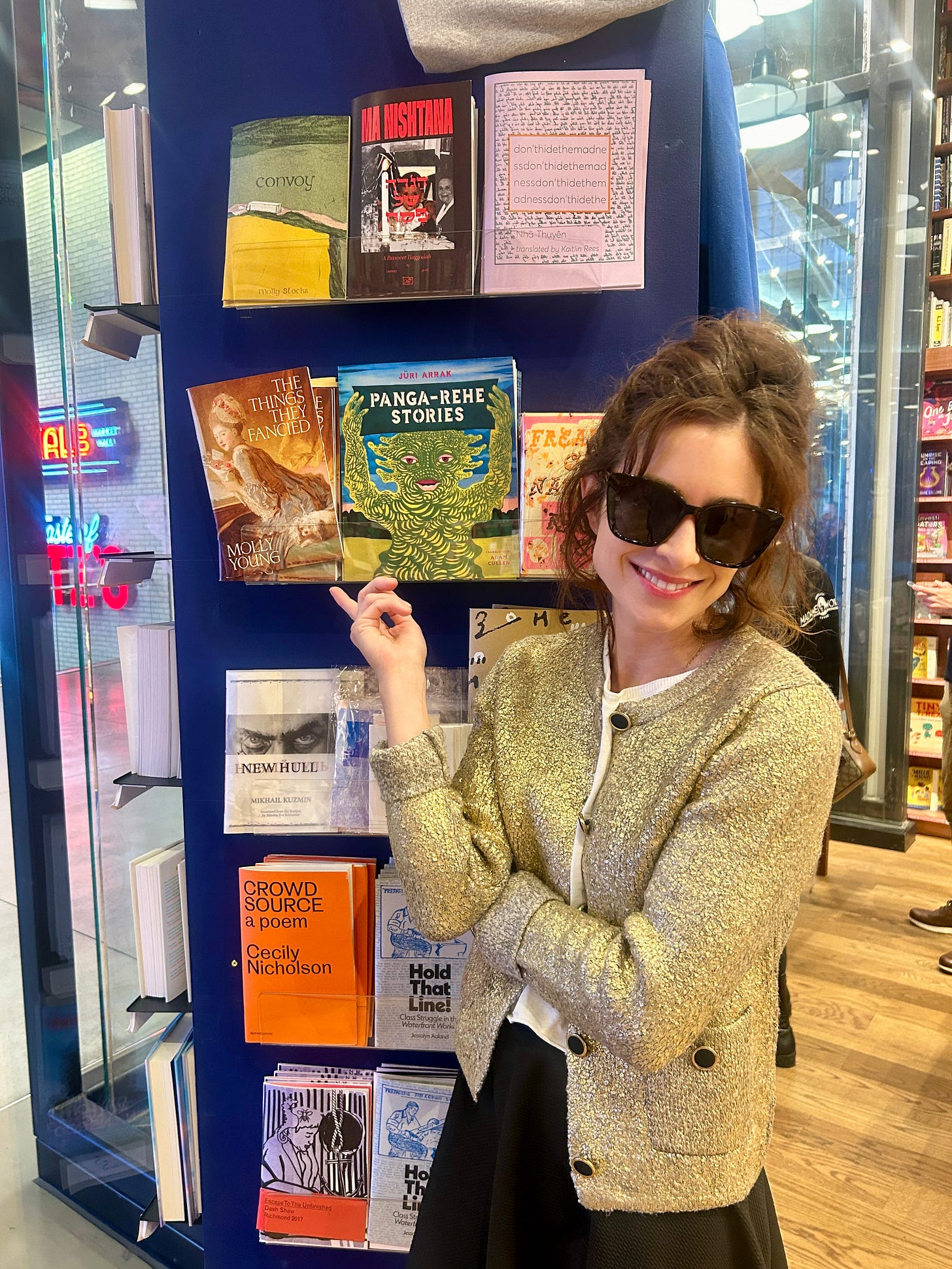

The TPF Q&A with writer Molly Young.

Molly Young is driven by curiosity. You never know where a conversation with the New York writer will lead. You start talking about gardening and the next thing you know you’re contemplating purchasing a hard-wired printer and never reading the newspaper on your phone again. Every time I talk with Young I leave with a list of scribbled down ideas, a good book recommendation, and some sort of harebrained scheme to change the world (or, at the very least, my internet consumption). I met Young years ago at Rupert Murdoch’s short-lived newspaper The Daily (RIP), where we worked on the features desk, played backgammon at Jimmy’s Corner after work, and tried, with varying levels of success, to convince publicists to let us profile their clients for an article that would only appear on an iPad.

These days, Young is a contributing writer at the New York Times Magazine where she writes features and essays like “My Miserable Week in the ‘Happiest Country on Earth’” and “The Mad Perfumer of Parma.” She publishes zines and books with her husband, the designer Teddy Blanks, via their eponymous company Young Blanks. And she writes the delightful newsletter The Life and Errors of

.Three Point Four Media called up Young to talk about gardening, work habits, and why surfing makes her a better writer.

Three Point Four Media: What are you obsessed with right now?

Molly Young: Not to be an old lady, but I am obsessed with gardening, which is obviously not ideal in New York City. But our apartment does get south and east exposure, so there's enough light that I can garden inside. It’s a real dopamine hack, because you get up every morning and you go to look at your plants and all of them have changed overnight in some way. Since I started growing plants, I’ve stopped shopping recreationally. There's something about plant husbandry that answers the need for the dopamine hit that online shopping used to provide. So that's good for the wallet.

It’s a good balm to the asynchronous nature of life nowadays, where you can do things via email or social media and you’re not existing in the same place and time as other people. Plants very much require you to exist in the same time and place.

There are so many other things to look at in New York besides my phone.

How are we working these days?

I'm completely dysfunctional when it comes to my attention span and habits, and every day is a battle to reform them. I have a little Post-it on my wall that I'm looking at. [Reaches for Post-it note.] It says “email three-to-five times a day.” So I only check my email three-to-five times a day. That’s a rule.

I have the Freedom app enabled on my computer, which prevents me from doinking around and doing bullshit. And I leave my phone bricked. The novelist Catherine Lacey told me about Brick. We met for a drink one night at Old Town, the great old bar in Union Square, and it came up that I had my phone on me but I always kept it off. I would carry around the phone in case of emergency, so it was this inert object in my bag. Brick is a little magnet you put on your fridge and can program it so that it turns your smartphone into a dumbphone.

There are so many other things to look at in New York besides my phone.

I started using the app Opal recently after I read

’s New Yorker piece. It’s like Nicorette for my phone. It’s shocking how effective these things are.1It's such a relief. You occupy a completely different temporal landscape when you're not running those things in the background of your mind.

Now that I have a kid, all of this makes me feel like an idiot or a baby; because it’s such a simple behavior modification. It’s like teaching a kid to say please and thank you and basically become civilized, and this is now what I have to do to keep myself civilized. The rewards are tangible enough that once you get past a certain threshold of anxious attachment and once you’ve discarded that it becomes easy and self-perpetuating. Have you found that?

I feel like I’m completely rewiring my brain.

I also find having a printer really helps. [Laughs.] The only good printers are Brother printers—that's a hot tip. I did a bunch of research. I've had a million printers. Brother printers are the best because they don't require a subscription. It's just a box that you plug in and out comes the paper. There’s no software and it’s not wireless. I wanted a printer that was not wireless because those things never work.

So I have a printer and if there’s something online I want to read, I print it out. I print out the crossword.

So we’re printing full articles?

Killing trees by the dozen, yeah.

Zines are a way of communicating a voice, perspective, and subject matter in a form that is accessible to produce and accessible to buy. It also offers a model of publication that is useful for people who couldn’t penetrate the big publishing world.

What’s next for you? You just left your post as book critic at the Times.

I left the books department, but I’m still on contract at the Times Magazine, which I have been for years now. The longer reported pieces and essays are more my speed.

Book reviewing was good. It was instructive to try it and find out that I'm not the best person for the job. It’s a difficult job and there’s a handful of people who do it really, really well. In the end, I’m not so interested in being an arbiter of things. I’m not interested in telling people what to read or not. I wanted to write more features. I wanted to write zines. I wanted to try to write a book.

What can we expect from Young Blanks? More zines?

I love the production model of zines. I think it's really interesting right now, especially because book publishing is always in a crisis. It’s a big unwieldy machine. It’s really difficult to get published if you’re an aspiring author and the hurdles and barriers to entry are so high and so opaque.

For me, the zine is this fascinating in-between object. It’s longform, but I put a lot of images and art into them. I’m very attentive to the design and typography. I care a lot about that stuff, as does Teddy, who designs them. Zines are a way of communicating a voice, perspective, and subject matter in a form that is accessible to produce and accessible to buy. It also offers a model of publication that is useful for people who couldn’t penetrate the big publishing world.

Our zines are sold in bookstores. We can print them in the U.S. They’re not super expensive to create. They’re definitely not lucrative, but they pay for themselves and at the end of the day I want somebody to pick it up and see a design detail or turn of phrase that will capture their attention and rewire their minds.

If I have something that doesn't fit into one of the available molds that that publishing offers, I just make it myself.

It’s also getting those voices out into the world.

It's true. There's also something special about the fact that this is writing that doesn't exist online. There's a line from the last Mission: Impossible movie—not the most recent one, but the one before that—where one of the characters, it might be Tom Cruise, says, “I have to go offline to a place where the entity can’t find me.” That’s the only thing I remember from that movie. There are certain things that should be reserved for an offline space where the entity can't find them.

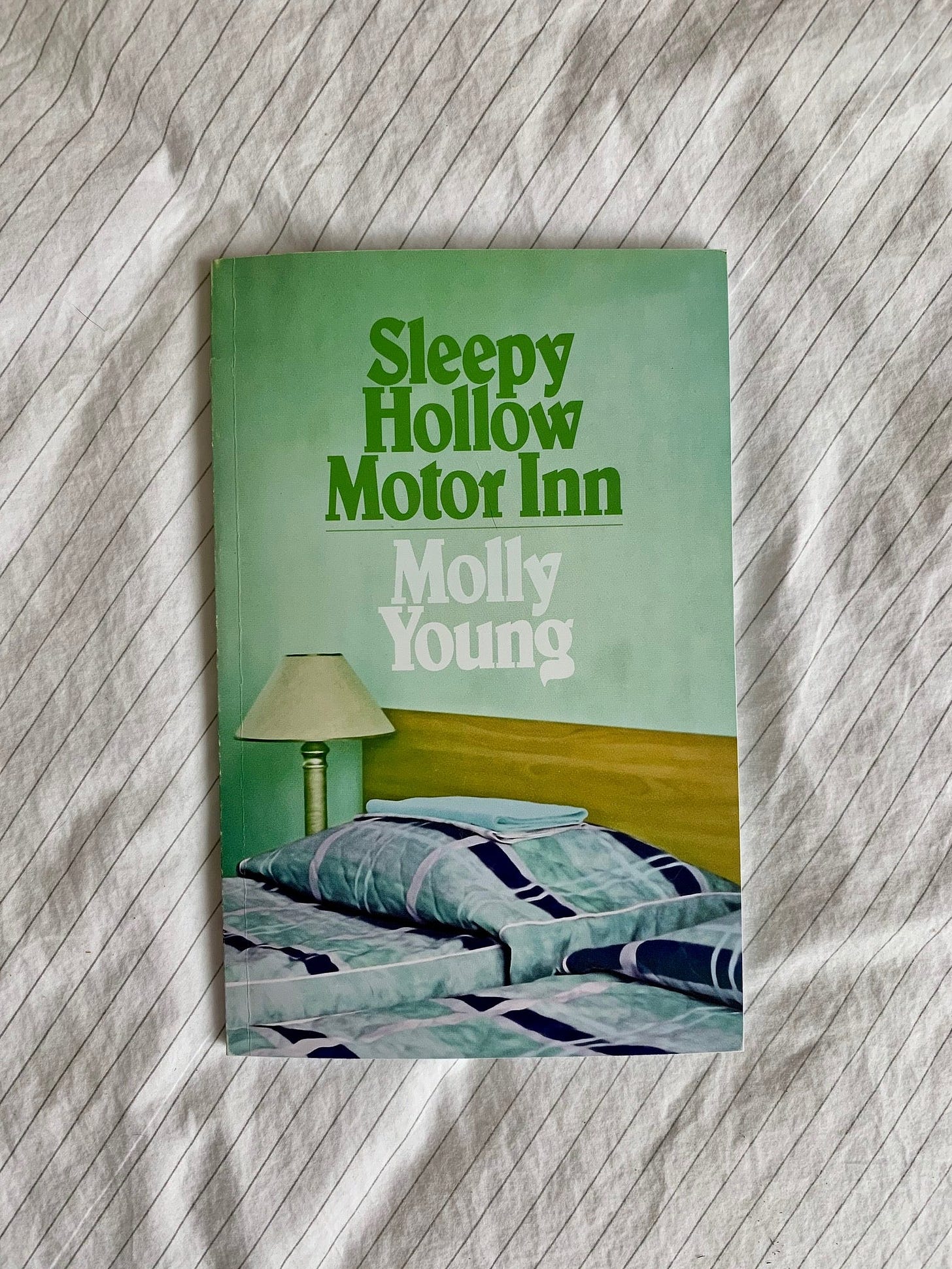

So for something like Sleepy Hollow Motor Inn, how do you decide what to take to your agent or editor vs. publishing it as a zine with Young Blanks?

Publishing has certain formats they're comfortable and equipped to handle. They can do novels. They can do big non-fiction books. They can do memoirs. There are certain conventions and word count ranges associated with each one.

Zines are these hybrid works where they're 10,000 words too long for a magazine story and far too short for a book. Sleepy Hollow was part investigation—I spoke with police and did a lot of reporting and archival work—and part Covid memoir. That's not a format that a publisher would really look at. So if I have something that doesn't fit into one of the available molds that that publishing offers, I just make it myself.

Surfing is good because it forces you to read nature in a way that's intellectually demanding: to think about the conditions and to manage your behavior among other people, other animals, and other forces.

What are you working on right now?

I’m working on a story for Harper’s about architecture, which is not something that I know much about. One of the privileges of writing for a great general interest magazine is they'll trust you to figure out a subject if you're not an expert in it. It’s kind of slow right now, honestly.

It’s that time of year.

I’m surfing. Although now there’s been shark sightings in the Rockaways. I moved away from California to get away from sharks. Why are they here?

I’m fascinated by surfing, but both risk averse and accident prone so I’ve never tried it. It seems like fly fishing or golfing where it’s this lifelong meditative pursuit and no matter what level you’re at you can always get better or learn something new about it.

Totally! It's very meditative. And you can do it well into old age, because you can do it in a way that's not super physically demanding. You go to Hawaii and there's, like, 80-year-old dudes who are sphere shaped out there shredding.

Never worn sunscreen, the color of deeply-tanned leather.

A mahogany! Surfing is good because it forces you to read nature in a way that's intellectually demanding: to think about the conditions and to manage your behavior among other people, other animals, and other forces.

It requires a different, animal kind of intelligence. I think it helps me as a writer. It forces me to pay closer and sharper attention to different things. Maybe that’s a way of deluding myself into thinking that surfing is somehow productive.

That makes sense. I’ve found that canoeing or fly fishing or running really helps reset my brain. You gotta get outside.

In my mind, the distinction is between hard thinking and soft thinking.

Soft thinking is when I'm outside, just kind of ambiently aware and receptive; that's where all the really good ideas come from. Hard thinking is when you're applying yourself like a tool or a boring instrument to a problem. You need both, obviously. But the soft thinking is where the magic happens and if you go too long without that you get dried up, man.

If you have an hour with somebody, you're going to write a Wikipedia entry with some great adjectives, if you're lucky.

Now that you’re freelance again, what does your relationship with editors look like, is it a mix of assignments and going to your editor at the Times Magazine and saying “I’m obsessed with this thing, I want to write about it”?

A bit of both, luckily. Most writers tend to write more interestingly and better on things they have some kind of native interest in. So the trick is to be interested in as many things as possible, to make yourself as perceptive and curious as possible—rather than having a very narrow pool of passions.

Do you still like writing profiles?

Love profiles. I do it less often, because even in the 15 years that I've been doing it, it's gotten harder. You have less access. Unless you’re Gay Talese, the strength of a profile correlates directly with the amount of access you have. So if you have an hour with somebody, you're going to write a Wikipedia entry with some great adjectives, if you're lucky. I will only do a profile if I can get some pretty serious access.

What is the minimum amount of access you need to write a celebrity profile?

More than two days. This is why I don't do celebrity profiles. I'm so demanding. [Laughs] I want to see them on set. I want to see them working.You have to see somebody at work. You have to observe somebody doing the thing that they do. And it's hard to get somebody to agree to that. They have very little reason to.

What celebrity do you want to profile badly?

Other people have made this point, but there are two ideal times to profile somebody: early in their career or at the end of their career. You want to get somebody when they have very little to lose.

If someone's at the end of their career, they've done what they need to do and they can speak more freely. They can let their freak flag fly a little bit more. If you have someone at the beginning of their career and they're quite hungry, they are more motivated to open up. But when you get someone at the mid-career point it's hopeless. You just get these canned quotes.

I feel like you can get access with someone whose last few movies were pretty bad.

Oh! Tom Cruise. He would be amazing to profile, because he's simultaneously a great American figure and a deeply bizarre man who is so private. I'm fascinated. I would love to know what makes him run, literally and figuratively. But Tom Cruise would never let me hang out with him for two weeks straight.

Changing gears. We came up in a totally different world where New York was more affordable and there were more opportunities. What kind of advice would you give to a young writer trying to break into the industry now?

We didn't know how good we had it back then! We came up with all these different outlets that helped writers hone their voice. I get a lot of questions from younger writers about how to develop their voice, and the only way to do that is to live an interesting life. Most frustrating answer, but it's also the most fun answer.

Some of those opportunities still exist. The difference is that there's very little guidance. So anyone can start a Substack, but then you're out in the wilderness without the benefit of an editor who will basically teach you how to write. When I wrote for the Observer,

taught me how to report a piece just by his editing. David Haskell at New York Magazine took me under his wing and in the act of editing my terrible drafts taught me how to write. If you're writing for Substack, you're not getting the benefit of a mentor.Self-publishing and Substack can be a real double-edged sword. A lot of writers don’t know how to self edit.

And you don't have the stamp of an institution to hide behind. You're ripping open your robe and shaking your whole naked self to the world. But if you’re willing to learn in public and distinguish between useful and useless feedback it’s possible to improve. There is a real value to putting out things that are a little bit rough around the edges. I don't see any shame in that. I think that can be quite interesting, to create an environment in which that's possible. And we're not just flogging people for a little misstep.

What you’re saying is you want 2011 Tumblr to come back.

Always. Always!

“Good work is what drives signups”

Dan Frommer stays ahead of media trends. He was Business Insider’s second employee—“There, I did a bit of everything: Reporting (5,700 posts)”—before serving as technology editor of Quartz and editor in chief of Recode. In 2019, he went out on his own, launching

After this interview I purchased a Brick and canceled my Opal subscription. It rules.

I love her